While catching up on news this weekend, I came across a press release dated 18 January 2024 from Quebec Precious Metals Corp (QPM) that caught my attention. The Company have just received assay results from a selection of grab samples collected late last year at their Ninaaskumuwin lithium prospect. The project is located on one of their Elmer East tenements.

‘Assay values from the nine samples from the discovery outcrop range from 1.10% to 3.92% Li2O‘

Note: Li2O = Lithium Oxide.

This is early stage stuff but I carried on reading. Then I came across this rather impressive picture of the Ninaaskumuwin outcrop.

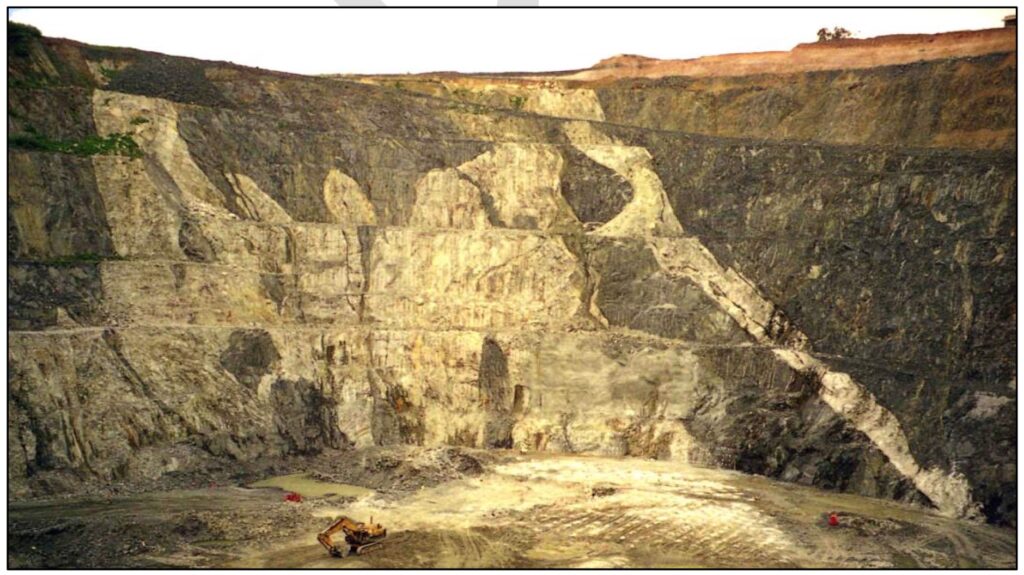

One of the helpful things about hard-rock lithium exploration is that you can often see the minerals that you’re exploring for. The same is often true when it comes to lithium mining. Take a look at this picture of the Greenbushes Lithium, Tin & Tantalum mine. You can see clear distinctions between the zones of pegmatite.

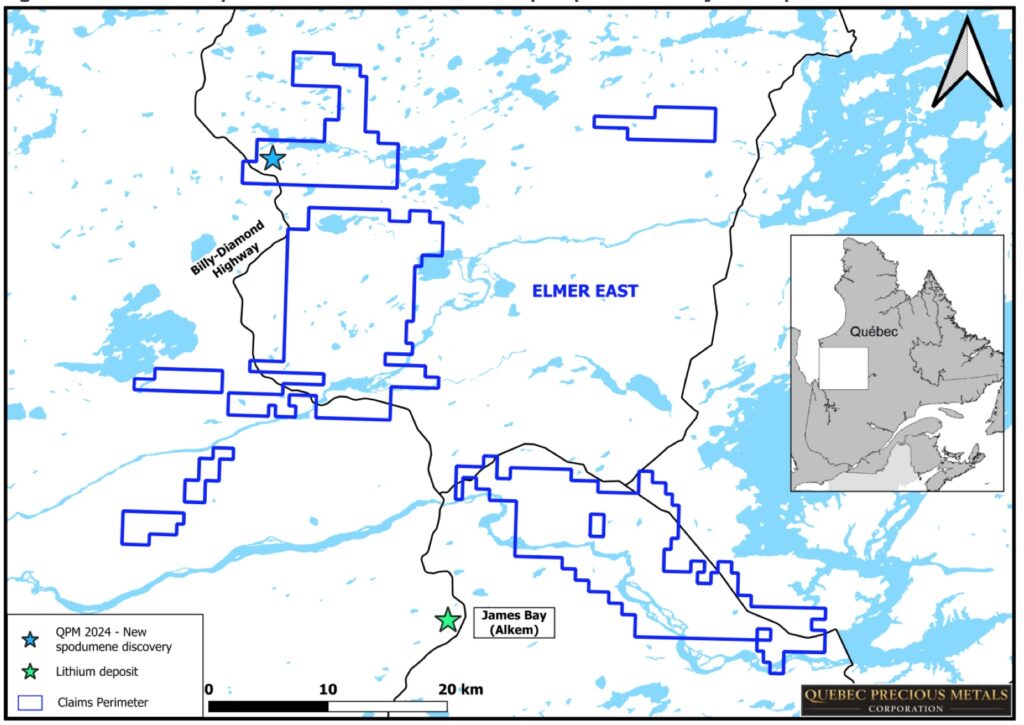

Going back to Quebec Precious Metals Corp’s Ninaaskumuwin outcrop. Here are some maps to help us get our bearings. The inset map on the right of the image below, shows the project area located on the east side of James Bay in Quebec, Canada. The blue star on the left of the image shows a more precise location of the project. Notice Allkem’s James Bay lithium project at the bottom of the image, approximately 45km to the south-east. Allkem – who have recently merged with Livent – have drilled out a mineral resource of 110 million tonnes at 1.3% Li2O at their James Bay project. The project is not under construction yet but an updated Feasibility Study was produced in September 2023. The estimated price tag to build Allkem’s project is US$381.5million.

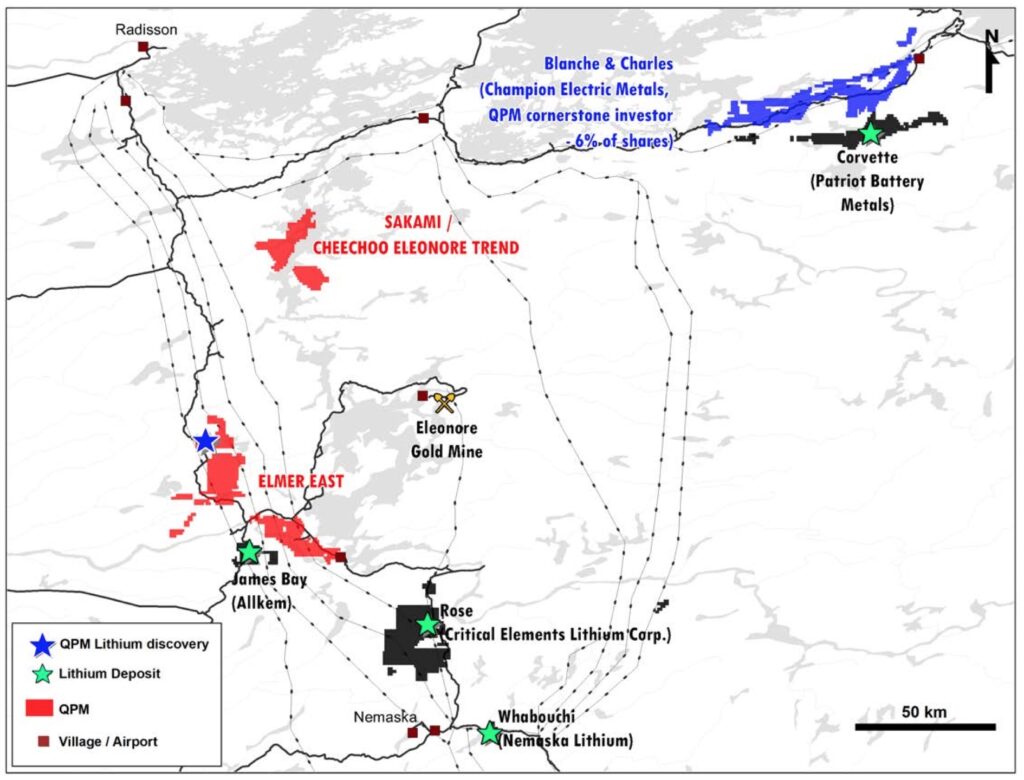

The below map zooms out a little further and shows other significant projects in the region. Notice Patriot Battery Metals‘ Corvette lithium project to the north east and Critical Elements Lithium Corp’s Rose project and Nemaska Lithium’s Whabouchi project to the south-east.

This is also gold country with extensive greenstone belts. Notice Newmont’s monster underground gold mine Éléonore, located almost due east. The mine produced 215,000 ounces of gold in 2022, with 1.6 million ounces remaining in Reserves at a grade of 5.2 grammes per tonne. As a side note, Newmont own shares in QPM. According to their investor presentation (page 4), ‘Management & insiders including Newmont Corporation’ own 16% but it’s unclear precisely how much Newmont own on their own.

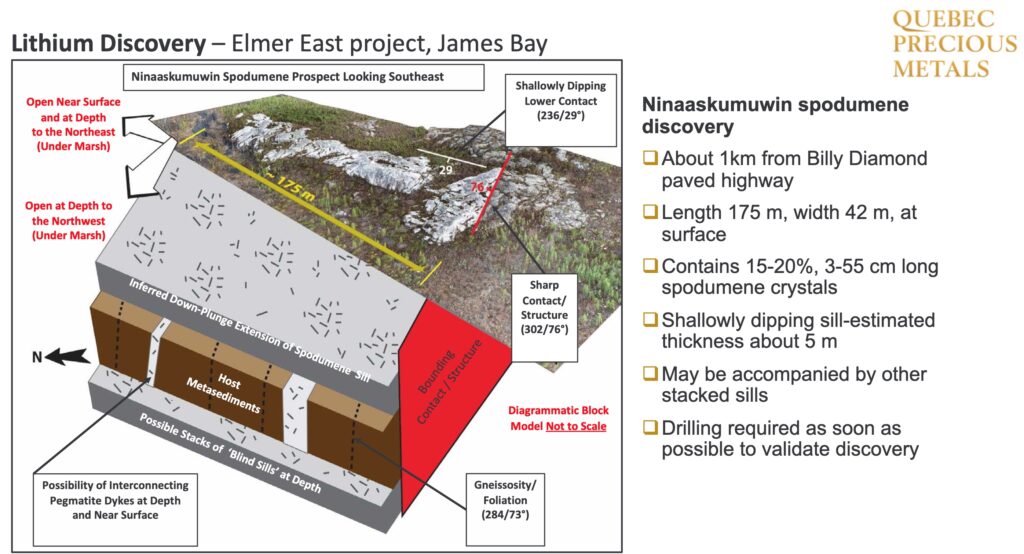

Going back to QPM’s Ninaaskumuwin outcrop, in the Company’s Winter 2024 Investor Presentation you’ll find the following slide. It shows the outcrop and the Company’s current guess at the direction the mineralisation is travelling in, below surface. They’re basing this on the structural controls they see at surface.

Note that the ‘sill‘ of mineralisation is believed to be 5m thick. In geology, a sill is a tabular sheet intrusion that has intruded between older layers of sedimentary rock or beds of volcanic lava.

And that the exposed outcrop ‘may be accompanied by other stacked sills‘. See the grey bit at the bottom of the image above labelled ‘Possible Stacks of ‘Blind Sills’ at Depth.

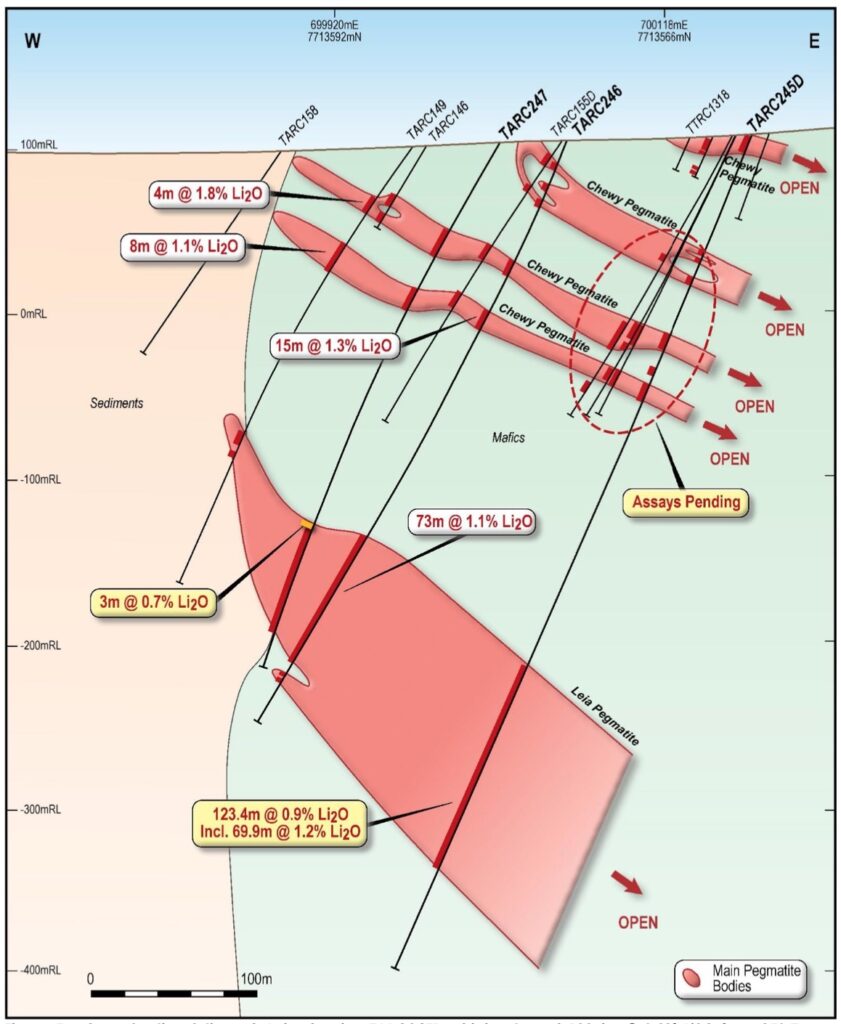

Now, this is all speculation as its very early stages but stacked sills are often found in lithium exploration. As an example, below is a cross section from Wildcat Resources‘ Tabba Tabba lithium project in Western Australia. Notice how the two pegmatite bodies in the top right come to surface, however these sills are stacked on top of other pegmatite bodies that have no surface expression at all. (To read more on Wildcat Resources exploration success click here)

Coming back to Quebec Precious Metals Corp’s Ninaaskumuwin lithium prospect, when they mention ‘may be accompanied by other stacked sills‘ this is what they mean. The large outcrop observed at surface MIGHT just be the tip of the iceberg.

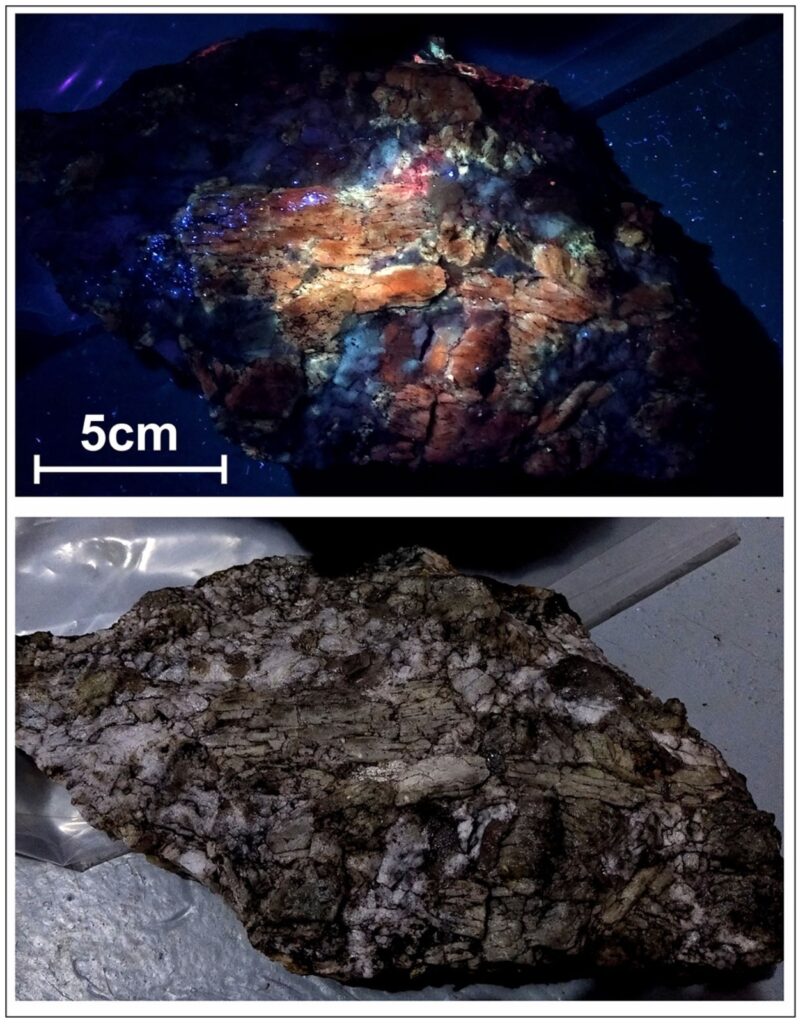

When exploring for hard-rock lithium mineralisation, Spodumene is the mineral that you want to find, since processing is relatively well understood and often easier than for other lithium-containing minerals like Lepidolite or Petalite. Spodumene fluoresces a reddish colour under exposure to ultra violet light and the blotches of reddish colour in the top image below suggests possible spodumene mineralisation. For other examples of spodumene fluorescing under UV light, read the article on Wildcat Resources.

Another interesting comment on page 21 of QPM’s Corporate Presentation is when they mention that the outcrop ‘contains 15-20%, 3-55cm long spodumene crystals‘. Evidence of large coarse-grained crystals is interesting because when it comes to processing spodumene mineralisation, coarse-grained spodumene is often easier to process into a concentrate.

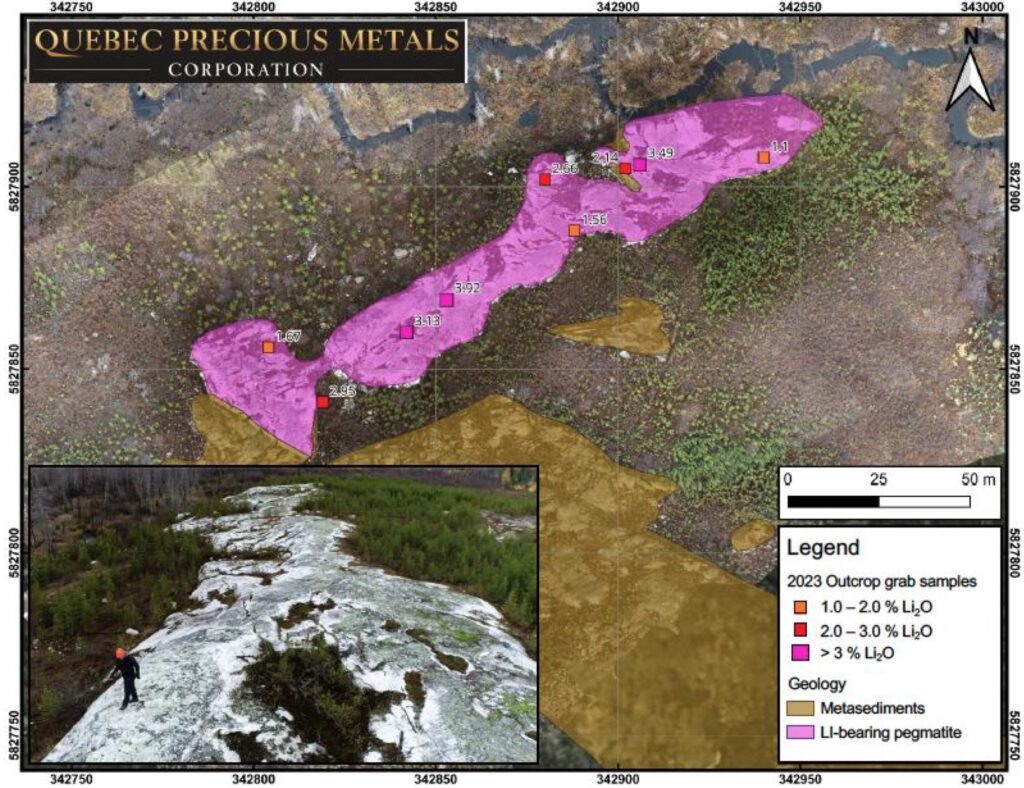

The news release on 18 January 2024, contained the following image that highlighted the location of the rock chip samples and their assay grades. The main image is an aerial view looking down on the outcrop.

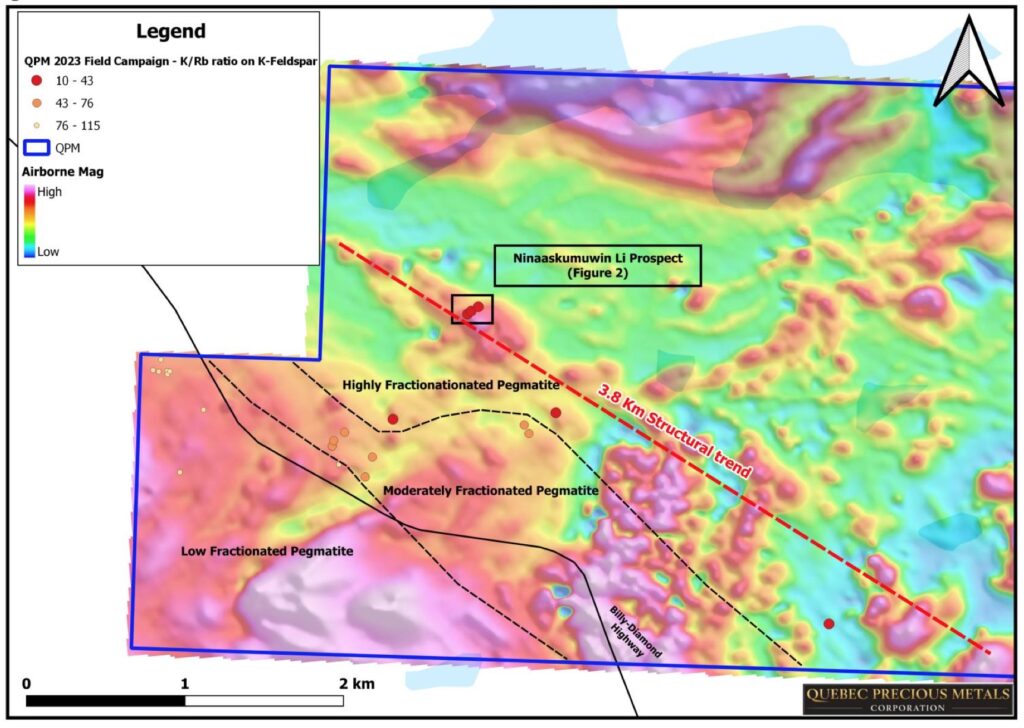

The news release also contained this map that shows ‘K/Rb ratios on K Feldspar‘. If you’re not an exploration geologist, you might wonder what on earth they’re talking about?

K/Rb ratios are often used in lithium exploration. K is the periodic table symbol for Potassium and Rb is the symbol for Rubidium. K-Feldspar (or Potassium Feldspar) is one of the main granitic pegmatite rock forming minerals.

All minerals in the feldspar group fit the generalised chemical formula:

X(Al,Si)4O8

In this formula, X can be any one of the following seven ions: K+, Na+, Ca++, Ba++, Rb+, Sr++, and Fe++. Feldspars that include potassium, sodium and calcium ions are very common. Barium, rubidium, strontium and iron feldspars are very rare.

Lithium deposits often form on the margins of granite intrusions. Granite itself is a coarse-grained intrusive igneous rock composed mostly of quartz, alkali feldspar, and plagioclase. It forms from magma with a high content of silica and alkali metal oxides that slowly cools and solidifies underground. Magmatic fluids, driven by the heat of the granite intrusion, can travel along structural cracks and faults in the earths surface, carrying alkali metals, like lithium, in solution. As the fluid slowly cools various metals are fractionated out of solution, in a similar fashion to how good ole whisky is distilled. If large enough quantities of minerals are fractionated out of solution, mineral deposits can form.

A paper by Trueman & Cerny (1982) looked at a number of ways to distinguish between rare metal bearing pegmatites from unmineralised pegmatites. They suggested the K/Rb ratio as one such tool as they pointed out that during late stage crystallisation caused by the fractionation process, Rubidium (Rb) has a tendency to substitute itself in place of the Potassium (K) in feldspar. They argued that a K/Rb ratio of less than 160 indicates increasing fractionation and ratios below 15 correlate to highly fractioned pegmatites often containing rare metal mineralisation, particularly Ta, Nb, Be, Cs & Li.

With this knowledge, take a look again at the map above with the K/Rb ratios and notice the area of highly fractionated pegmatite. This is the region worth exploring first.

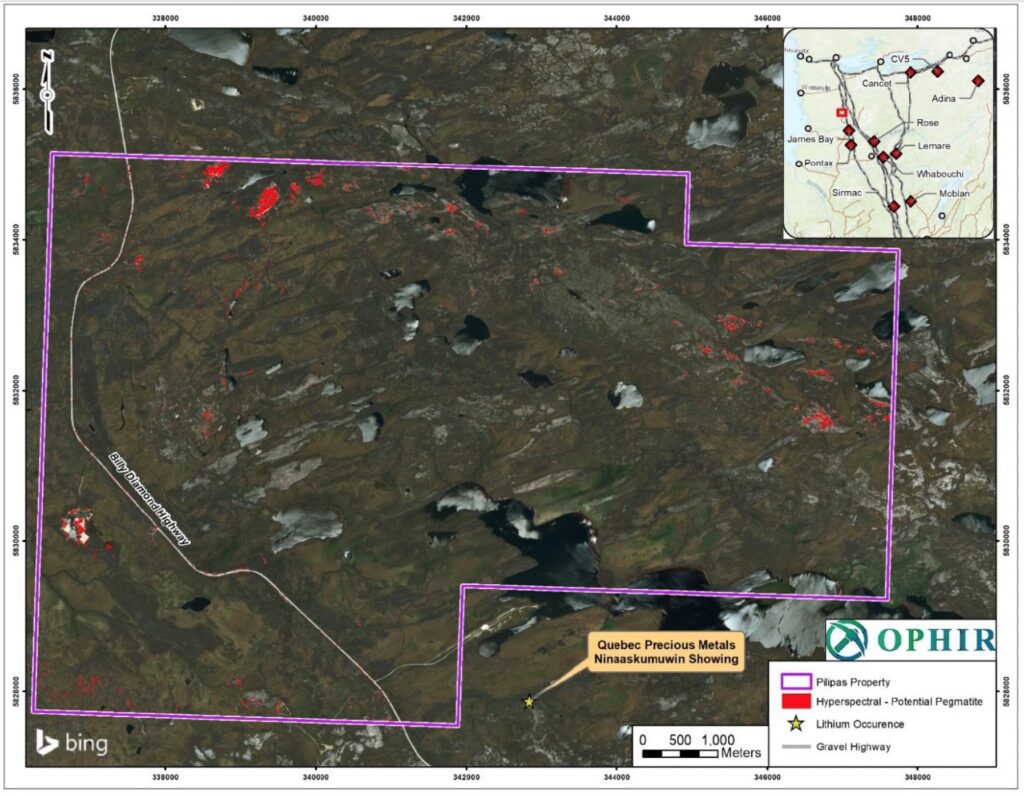

As a brief side note, it’s worth mentioning that Ophir Gold own the tenement to the north of QPM’s project, in the direction of the increasingly fractionated pegmatite. Here’s a slide of Ophir Gold’s Pilipas Lithium Project boundary.

Now, I must reiterate that this is all very early stage exploration but what also interests me is the fact that Quebec Precious Metals‘ market capitalisation is only approximately C$5million (19 January 2024).

The lithium exploration sector is currently in a malaise due to the rapid decline in lithium chemical prices. Perhaps the news got somewhat overlooked when the discovery was first announced in October 2023? I’m not entirely sure. But for me, this is an interesting time to look at some of these lithium explorers.

QPM, according to their 18 January 2024 release, is planning to:

- perform a diamond drilling program that aims to test the down-dip extent of the sill of the discovery outcrop, and the presence of potential stacked sills; and,

- carry out geological mapping in and around the discovery outcrop and collect additional structural measurements.

I plan to keep an eye on developments with Quebec Precious Metals’ Ninaaskumuwin lithium prospect.