Written by Roger Breuer, ACCA. Additional Research by Willem Middelkoop.

At Commodity Discovery Fund a key consideration for any investment is scale. When considering this important factor, we ask ourselves – ‘Does a mineral discovery have the potential to grow further? And is it possible that more deposits are found at depth or nearby?‘ If we acquire the initial discovery cheaply enough then these ‘options’ on further discoveries can generate outsized returns for our investors.

An example of this potential for ‘scale’ is provided by the historic Silver Queen Mine located in Superior, Arizona. In 1880, the Silver Queen Mining Company started to dig the silver-bearing veins that were exposed at surface. They chased the veins underground where the silver mineralisation decreased, but showed increasing signs of copper mineralisation. By 1893 the most profitable silver had been mined, and the drop in silver prices from US$1.50 per oz to US$0.20 per oz caused by the financial ‘Panic of 1893‘ and the repeal of the Sherman Silver Purchase Act led to the closure of the mine.

In 1910, William Boyce Thompson and George Gunn, became interested in the Silver Queen Mine’s copper potential and bought it for US$130,000. They incorporated the Magma Copper Company and renamed the mine Magma. Exploration efforts pushed deeper underground and it soon became evident that ‘small, irregular, rich chalcocite (copper ore) zones that had first been encountered at shallow levels became more continuous with depth.’ (Hammer and Peterson, 1968).

By 1916, development activities encountered the Magma Vein, which the Arizona Geological Survey described as follows; ‘Mineralised from wall to wall at that point, this high-grade zone was 34 feet thick, and averaged 10.5% copper, 5.4 oz per ton silver and 1.3 oz per ton gold.’

Magma was showing itself to be a powerful geological system. The mine operated until 1996. ‘Over the 86-year life of Magma Copper’s Superior Project (1911-1996), approximately 26.7 million short tons of ore averaging about 4.9% copper were mined, recovering 1,299,718 short tons of copper, 36,550 short tons of zinc, approximately 686,000 ounces of gold and 34.3 million ounces of silver.’ (Arizona Geological Survey).

But this system wasn’t done yet. By 1996, Broken Hill Proprietory Limited (BHP) owned the Magma mine. Over the following years, Rio Tinto earned into the project and they set about exploring for the driving force behind this mineralisation. Eventually, in 2004 the Rio Tinto (55%) and BHP (45%) joint venture – called Resolution Copper – found the porphyry at depth and have so far drilled a resource of 1.8 billion tonnes of ore at 1.5% copper. The porphyry contains a staggering 27 million tonnes of copper which once in production is expected to provide 25% of the US’s copper requirements.

As a side note, William Boyce Thompson went onto create a holding company for his mining assets. The holding company was called the Newmont Mining Corporation, a company whose early years owe much to the outstanding success of Magma.

The Silver Queen Mine is what we mean by ‘potential for scale‘.

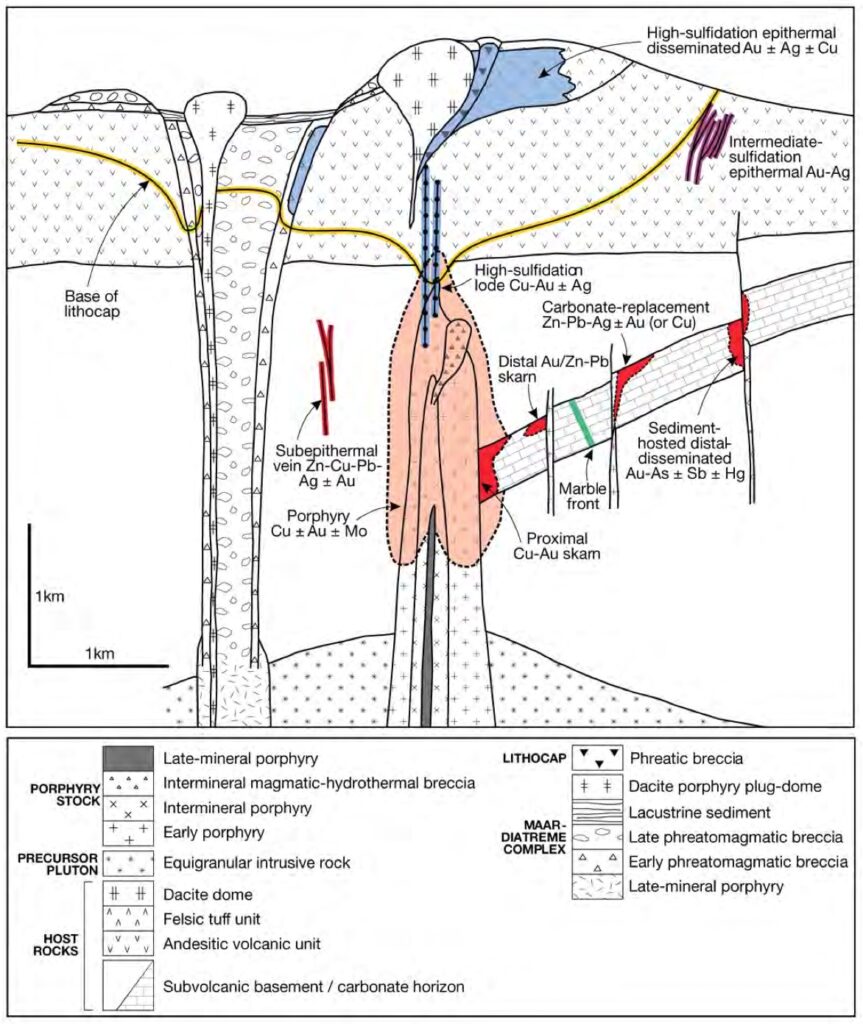

Our understanding of these geological systems today is a world away from our knowledge back in the late 1890’s. It wasn’t until the seminal work of geologists like Gilbert and Lowell (1970) and Sillitoe that we started to understand the anatomy of these systems and how high, intermediate and low sulphidation deposits near surface are genetically linked to porphyry systems at depth. This ground breaking work in the 70’s and 80’s no doubt guided Rio Tinto and BHP’s exploration for the Resolution porphyry.

The following diagram by the great geologist Richard Sillitoe is a generalised model of how porphyries, often containing copper, gold and molybdenum, are genetically linked to various other types of deposits like; skarns, carbonate-replacement deposits (CRDs), high-sulphidation lode copper, sediment hosted gold, as well as high, intermediate and low sulphidation epithermal gold and silver type deposits. There’s a lot to digest here but the key point is that geologically these deposit types are often inter-linked.

Take your time to locate the Carbonate Replacement Zn-Pb-Ag+-Au (or Cu) mineralisation shown in the image above – follow the brick pattern on the right of the image – as this will be relevant to our discussion of Tinka Resources.

When the magmatic intrusion forms a porphyry (light pink colour in the image above), hydrothermal acidic fluids containing dissolved metals start to find their way through cracks in the surrounding rock, driven by the heat and pressure of the molten intrusion. When these fluids reach the sedimentary layers of carbonate rock, they react. As Putnis and John (2010) explain, a two stage process takes place. The acidic solution eats away at the calcium carbonate rock creating a tiny void. Since the calcium carbonate is alkaline in nature it neutralises the hydrothermal solution which causes the metal sulphides to precipitate out of solution. If enough metal precipitates out of solution a ‘manto’ of ore is formed. This essentially is a Carbonate Replacement Deposit (CRD).

Armed with this understanding of geology we can now take a look at Tinka Resources.

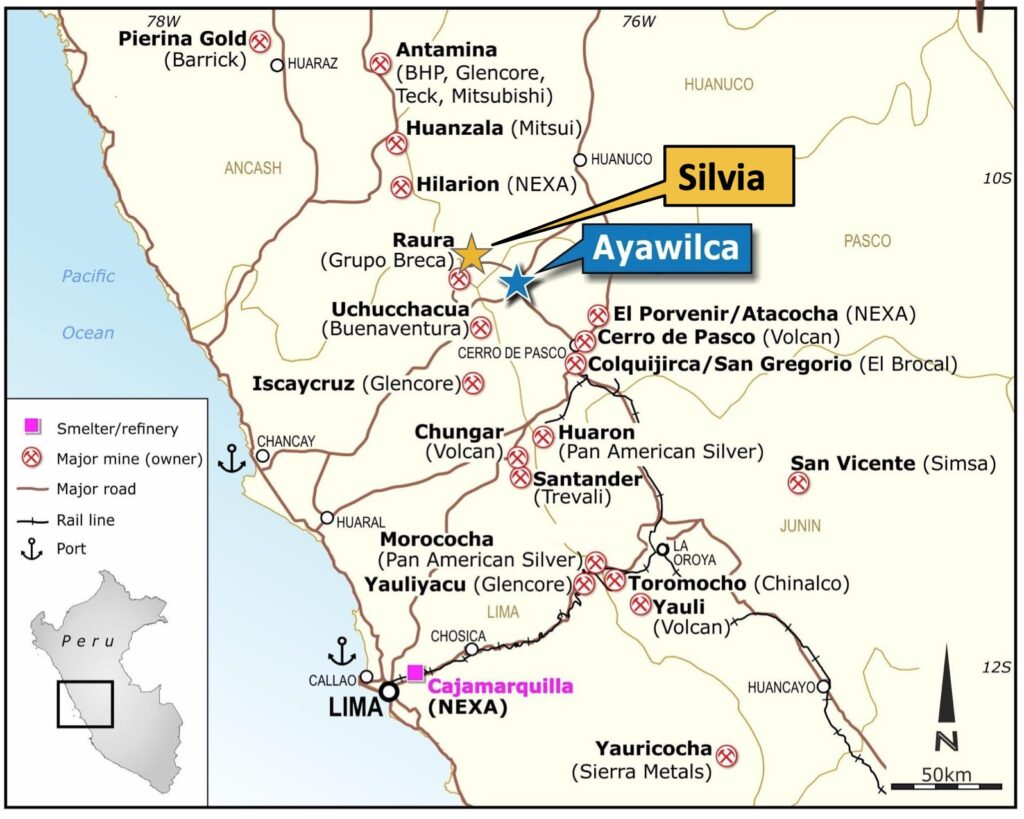

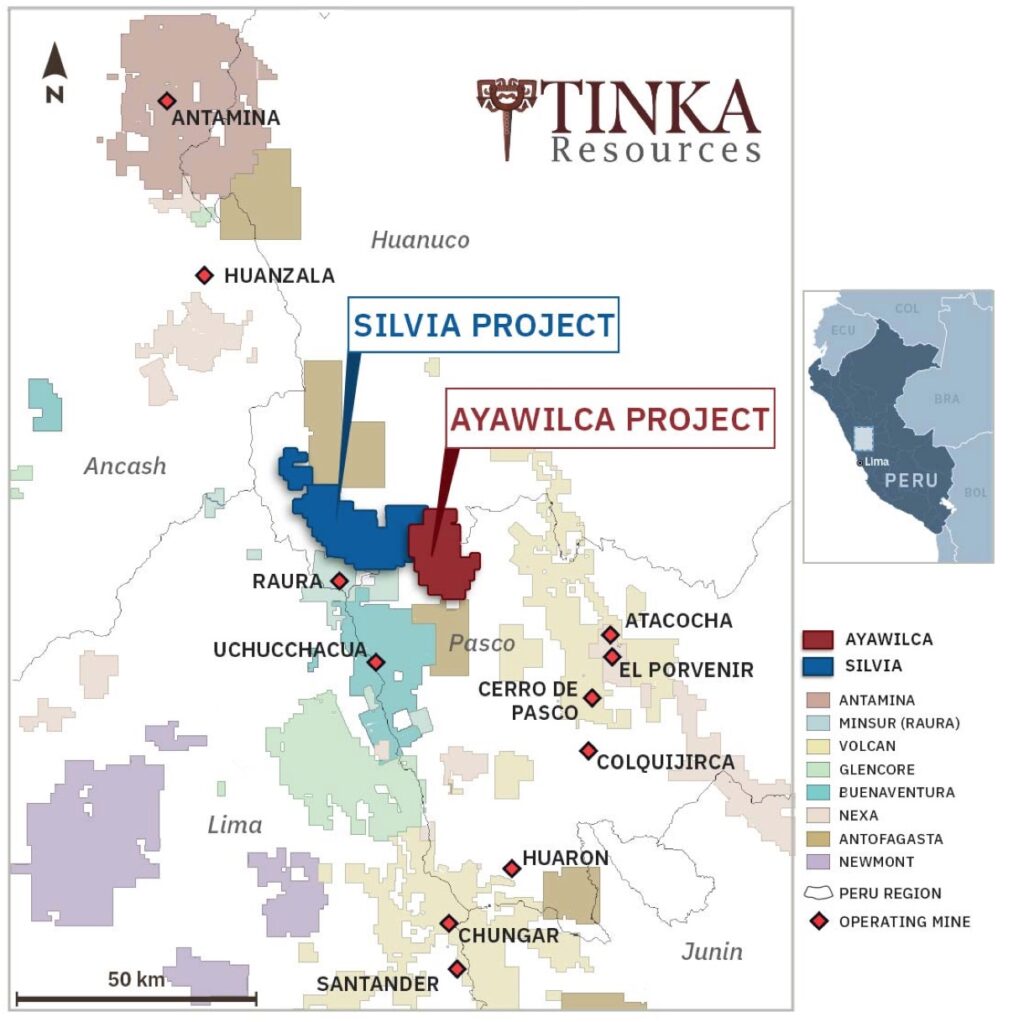

Tinka Resources, led by geologist Dr Graham Carman, owns the Ayawilca and Silvia projects in Peru. We’re going to focus on their flagship project Ayawilca for now but we’ll come back to Silvia.

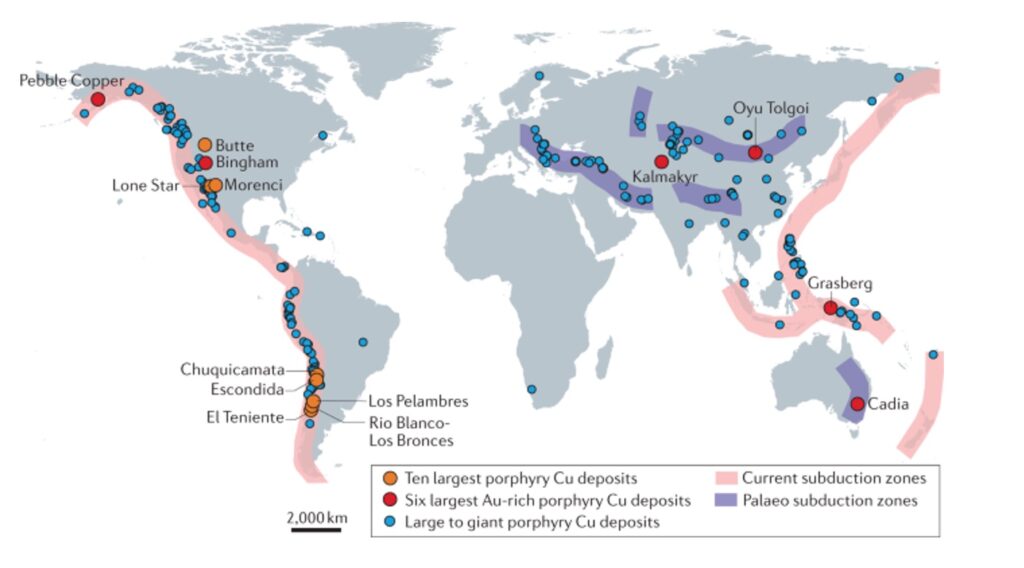

Peru is prime mineral country and there’s a reason why. Look at all of the porphyry deposits (see below) that have been found along the western edge of the Americas. Notice Morenci, a giant mine located in Arizona owned by Freeport. Morenci is only a couple of hours drive from Superior, Arizona, the location of the Silver Queen Mine.

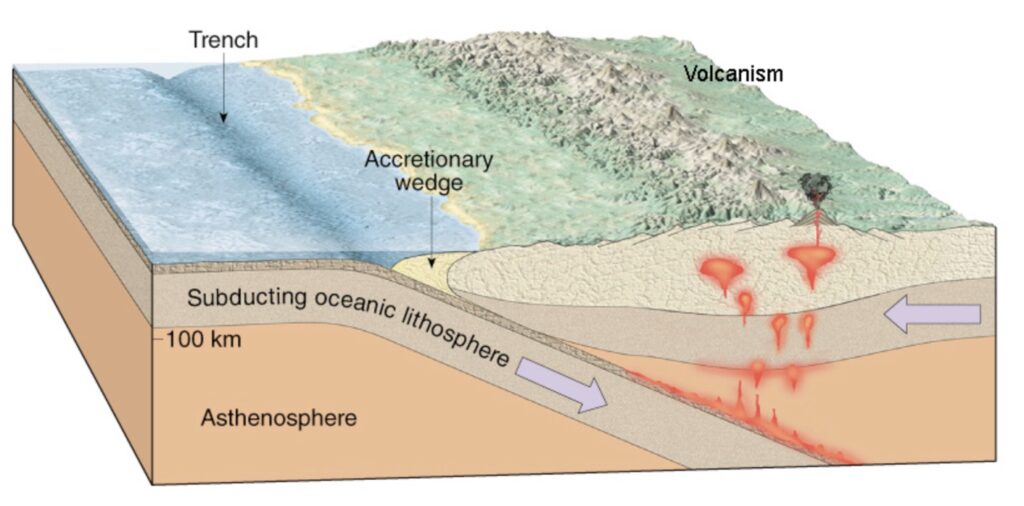

The reason for the proliferation of deposits along the western edge of the Americas is the increased volcanism caused by the convergent plate boundaries. Where tectonic plates collide, one plate is subducted under the other. Notice the red blobs of molten magma on the right of the image below caused by the melting of the subducted plate. These magmatic intrusions then rise up, like blobs of wax in a lava lamp, through weaknesses in the earth’s crust carrying minerals in solution and forming deposits.

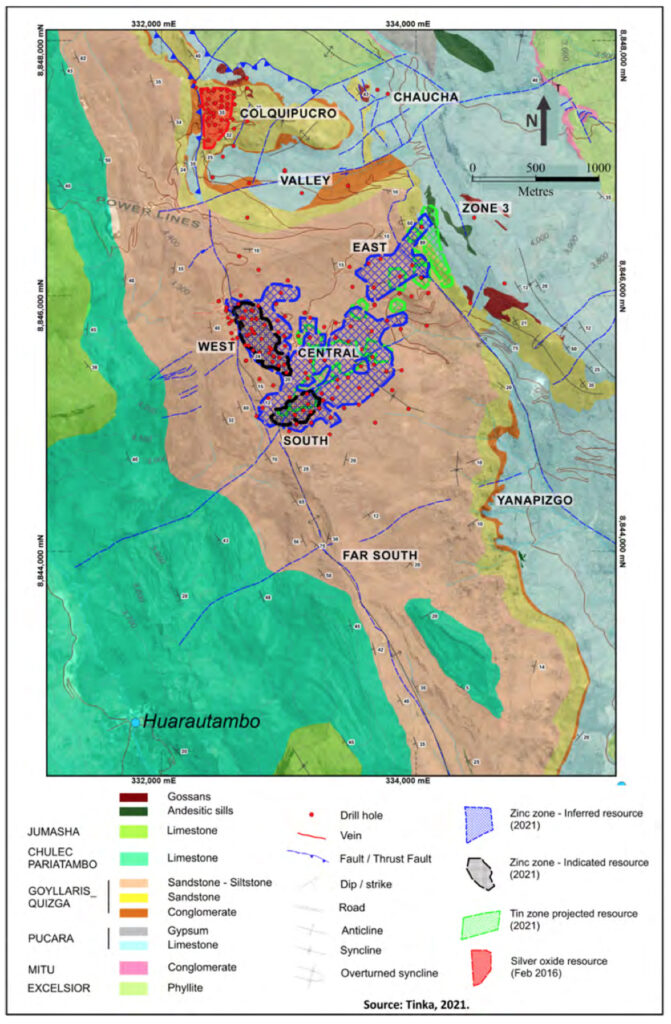

At their Ayawilca deposit in Peru, Tinka Resources have found a large polymetallic deposit of zinc, silver, lead and tin. According to the technical report released in 2021, ‘the geological setting, deposit geometry, and style of mineralization indicates that Ayawilca is a Carbonate Replacement Deposit (CRD).’ In the plan view (looking down) of Ayawilca shown below, notice the large patches of limestone (aka calcium carbonate) denoted by the darker green on the left and lower left of the image. The zinc deposit is denoted by the blue and black patches. Lead is also present. The silver is denoted by the red patch at the top and the tin is denoted by the hatched bright green patch around the East and Zone 3 labels.

A New Technical Report for Ayawilca Highlights the Economics

On 28 February 2024, Tinka Resources announced the summary of an updated Preliminary Economic Assessment (PEA) for the project.

The significant differences between the recently updated PEA (2024) and the previous PEA (2021) includes:

- The introduction of a separate tin plant to process the tin resource.

- A reduction in the processing ambitions of the project. The 2021 PEA envisioned a processing capacity of approximately 3.1 million tonnes per year of zinc/silver/lead ore. The updated PEA (2024) envisions processing 2.0 million tonnes per year of zinc/silver/lead ore and 0.3 million tonnes per year of tin ore.

- A revised Mineral Resource statement incorporating 11,000 metres of drilling completed in 2023.

- The updating of cost estimates to incorporate the inflationary effects since 2021.

We particularly welcome the lower processing ambitions of the project as a way to reduce execution risk. The processing plant can always be increased in scale at a later date. Additionally, given recent inflationary pressures, we welcome updated costs, to get a clearer picture of economics.

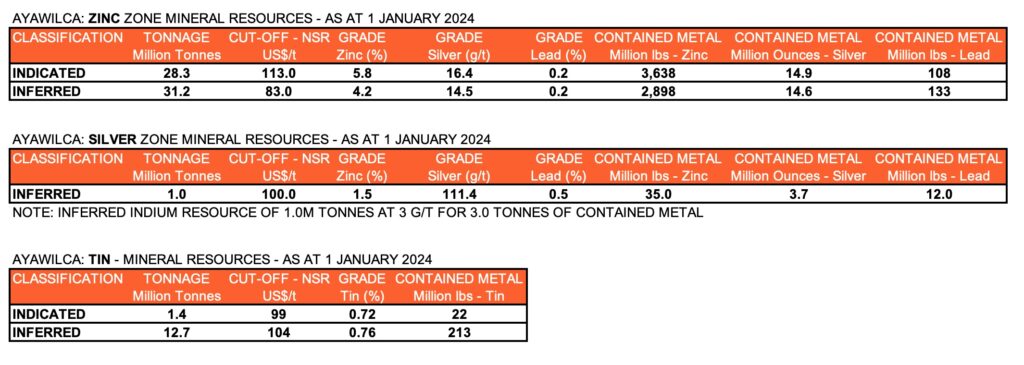

The revised Mineral Resource statement now shows approximately 3.6 billion lbs of zinc in the Indicated category at a grade of 5.8% Zn, with a further 2.9 billion lbs of Inferred Material. 14.9 million ounces of silver in the Indicated category with a further 14.6 million ounces of silver of Inferred material.

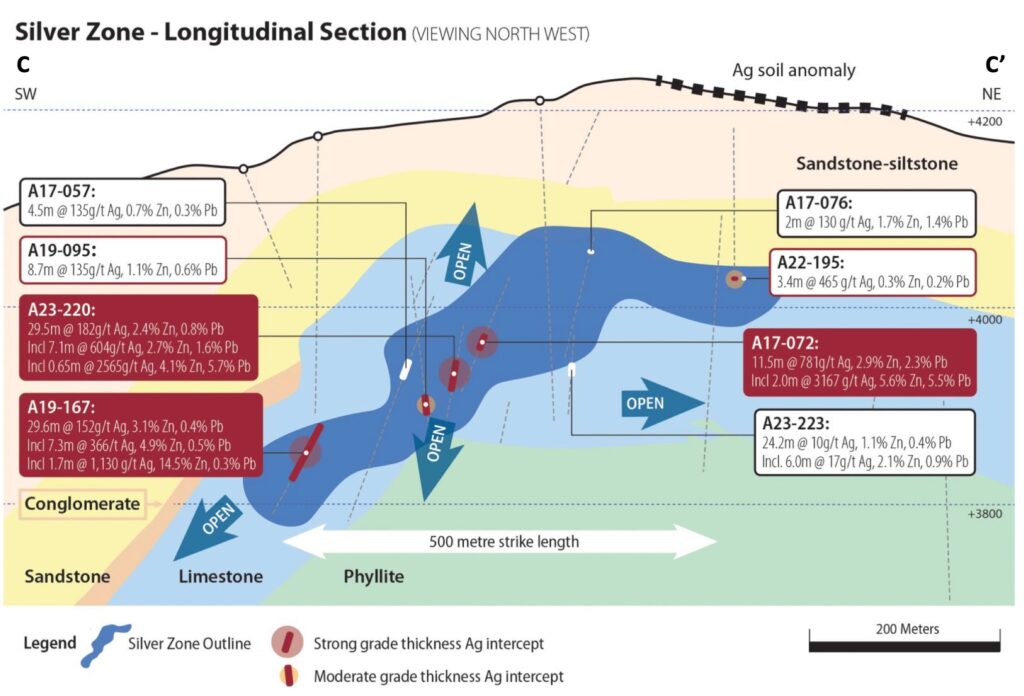

A separate high-grade silver zone has been drilled out to an Inferred category with 1.0 million tonnes of ore at 111.4 g/t Ag, containing 3.7 million ounces silver.

A tin resource has also been defined showing 22 million lbs of tin in the Indicated category at a respectable grade of 0.7% tin, with a further 213 million lbs of tin in Inferred.

For those interested, the detailed Ayawilca Mineral Resource Statements as at 1 January 2024 can be viewed here.

Polymetallic deposits, by their very nature can have quite a few moving parts. Detail is of course important and for those looking to delve deeper, we point out that the previous Ayawilca Technical Reports can be found on Tinka’s website. Also, the full technical report for the recently updated PEA (28 February 2024), will be published on Sedar within 45 days following the announcement.

For the purposes of this article, we’ll move straight to the economic implications of Ayawilca. As investors, ultimately we’re interested in the intrinsic value of the project.

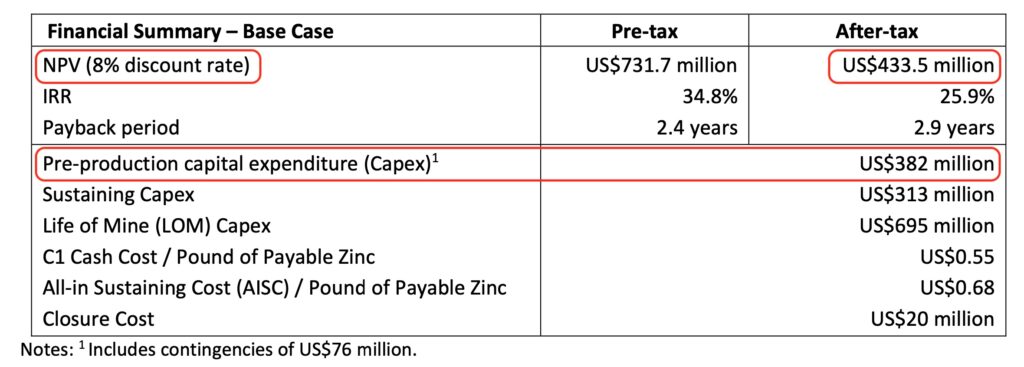

The updated Preliminary Economic Assessment (PEA) for Ayawilca has estimated an Net Present Value (NPV) at an 8% discount rate and after tax of US$433.5million, based on long‐term metal prices of US$1.30/lb for zinc, US$1.00/lb for lead, US$22.00/oz for silver and US$11/lb for tin.

Tinka Resources’ current market capitalisation is approximately C$39.4million (as at 2nd March 2024), with C$7.5million of cash according to the last reported balance sheet as at 30 September 2023. We must also consider financing requirements for the project but Tinka’s market capitalisation is significantly below initial estimates of intrinsic value, as gauged by the PEA. And this is before we consider the size of the project growing.

Further Exploration

While the Ayawilca project is progressing steadily and the economics appear comfortably favourable, a key area of interest for us remains the ongoing exploration potential.

Consider this statement from Tinka Resources’ President and CEO, Dr Graham Carman;

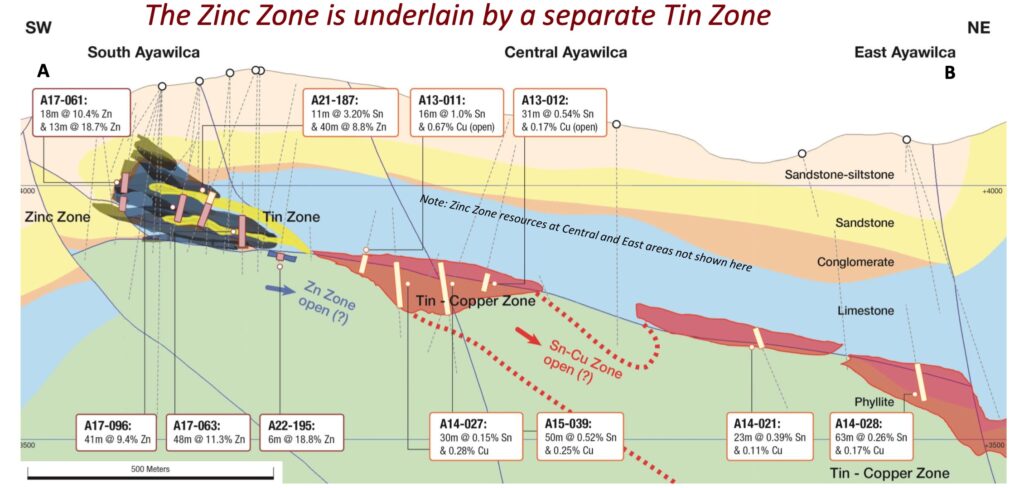

“There remains significant exploration potential for further discoveries at Ayawilca, and several of the resource bodies remain open at depth, with a potential feeder system remaining largely untested by drilling particularly at the Tin Zone.” (28 February 2024 News Release)

The news release goes onto describe;

“Opportunities for additional value at Ayawilca not captured in the PEA include, but not limited to:

- Potential to extend the Zinc Zone deposits to depth at the East and West areas with more drilling;

- Potential to extend the Tin Zone to depth at the Central area, in particular where a steeply‐dipping feeder zone is interpreted and is untested by drilling;

- Potential to extend the Silver Zone along strike and at depth – only 500 m of strike length is tested to date;”

There’s much still to drill and this follows on from some remarkable drilling last year. Of the 11,000m drilled in 2023, here are some highlights:

- 98 metres at 8.8% zinc including 36 metres at 19.0% zinc

- 71.9 metres at 5.5% zinc & 8 g/t silver including 45.8 metres at 6.4% zinc & 10 g/t silver

- 30.4 metres at 6.0% zinc including 1.2 metres at 37.2% zinc

- 145.2 metres at 10.9% zinc including 29.3 metres at 20.2% zinc

- 4.6 metres at 32.4% zinc

- 29.5 metres at 182 g/t silver, 2.4% zinc & 0.8% lead including 7.1 metres at 604 g/t silver, 2.7% zinc & 1.6% lead

These high grade zinc and silver intervals, in some cases in excess of 30% zinc and half a kilo per tonne silver, point to the powerful nature of this geological system.

The following figure shows a cross-section through the silver zone, which remains open in all directions.

The following cross section focuses on the tin zone that lies below the zinc zone. Notice the dotted red lines that shows a region of copper mineralisation which remains open at depth. The copper mineral found is predominantly chalcopyrite.

Remember Richard Sillitoe’s Generalised Model for CRD – Porphyry Deposits from earlier. It would seem logical for us to ask – if there’s evidence of a copper porphyry lurking nearby and driving this powerful Carbonate Replacement Deposit (CRD)?

The Silvia Project

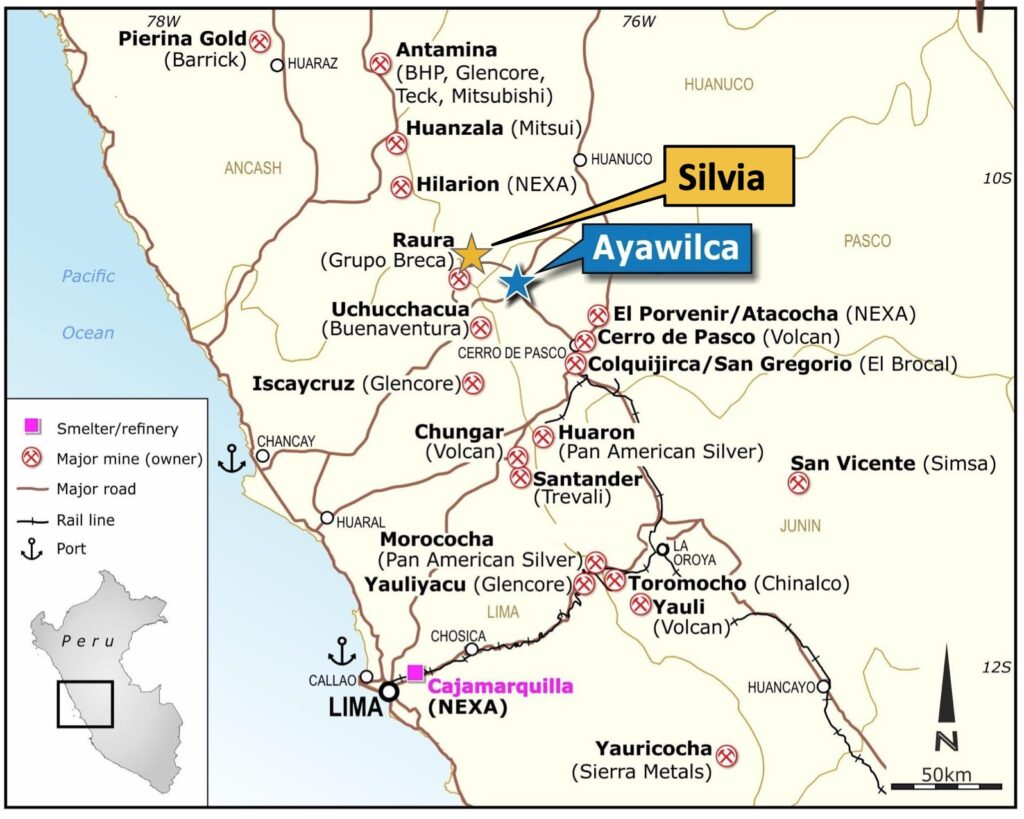

We promised that we’d come back to Tinka’s Silvia project, which Tinka refer to as their Silvia Copper-Gold Project. In July 2021, while many of us were under lock-down restrictions, Tinka were busy with lawyers acquiring the Silvia project from BHP. The project is contiguous with their existing Ayawilca project.

Dr. Graham Carman, the CEO of Tinka, commented at the time: “The Silvia Project acquisition fits in very well with Tinka’s vision of exploring for potential world‐class base and precious metal discoveries in Peru. Tinka considers the Silvia Project to be highly prospective for large copper skarn and porphyry deposits, and we are thrilled to have acquired this exciting portfolio from BHP right next door to our flagship Ayawilca project. This acquisition triples the size of Tinka’s mining concessions in central Peru, turning the Company into one of the largest landholders in this highly mineralized belt. The target limestone at the Silvia Project is the Jumasha Formation which hosts the giant Antamina skarn deposit, while the Ayawilca deposit is hosted by the Pucara limestone.”

Antamina is a huge copper zinc mine jointly owned by Glencore (33.75%), BHP Billiton (33.75%), Teck (22.5%), and Mitsubishi Corporation (10%). In 2022, it produced 452,000 tonnes of copper in concentrate, 428,000 tonnes of zinc in concentrate and 14.7 million ounces of silver in concentrate. It’s a behemoth. The zinc production makes it the largest zinc producer in the world, according to 2020 data. Notice its location to the north west of Tinka in the map above.

The ore body at Antamina is classed as a skarn-type deposit. Go back to Richard Sillitoe’s geological model (above) and spot the skarn mineralisation – both proximal and distal – related to the porphyry intrusion. This is how skarns fit into the geological jigsaw.

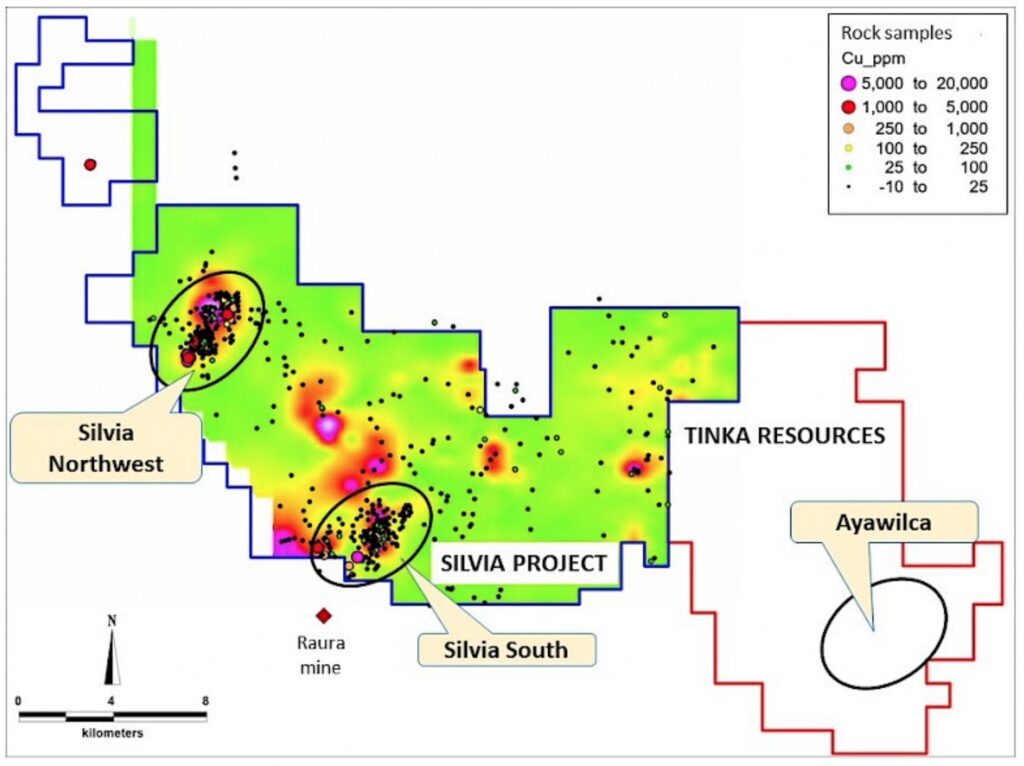

The Silvia tenement has two areas where elevated copper readings from rock samples correlate with magnetic anomalies. Magnetic anomalies might suggest the intrusive rocks we’re looking for. ie copper porphyries.

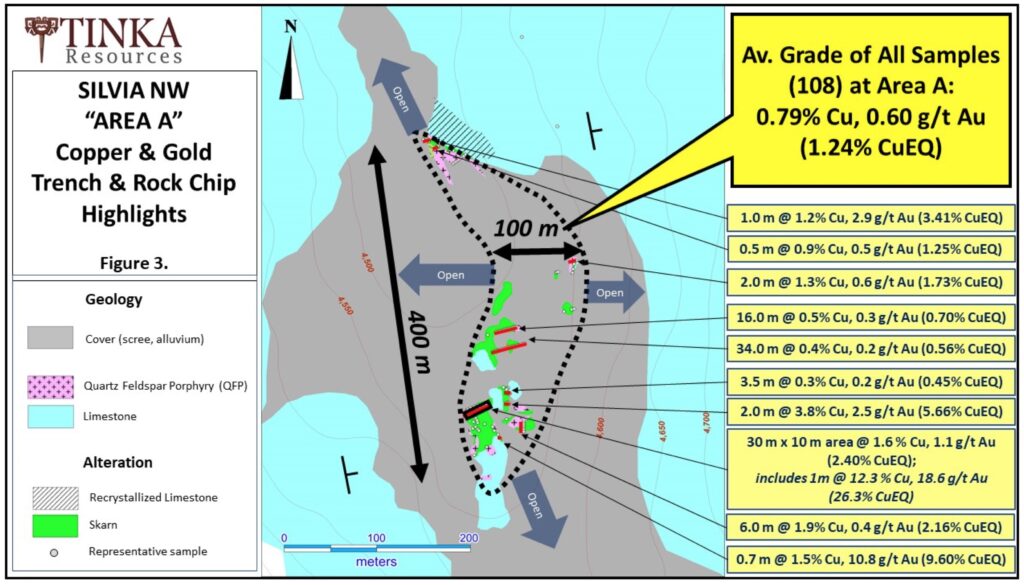

Trenching work focussed on Silvia NW showed significant copper and gold mineralisation. The pink areas in the map below denote porphyry rock and the green areas denote skarn rock.

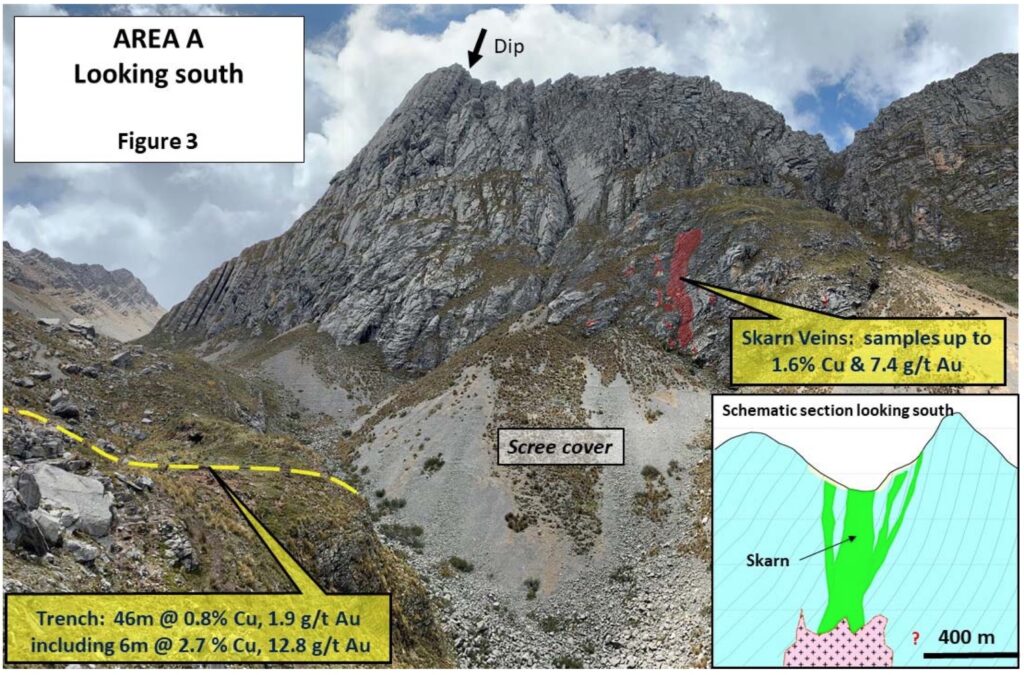

An announcement in early 2022 highlighted the discovery of skarn veins in limestone and declared some excellent trenching results of 46m at 0.8% copper and 1.9 g/t Au.

Notice the diagram in the bottom left hand corner of the image above and the ‘?’ by the pink blob. This is the correct question to be asking. ‘What’s driving this mineralisation found at surface?’

In our opinion, the exploration potential at both Ayawilca and Silvia is significant.

Shareholder Support

Tinka Resources has a project at Ayawilca that’s shaping up remarkably well economically, as it continues to grow. It’s little surprise to us that the Company has attracted Buenventura (19%) and Nexa Resources (18%) onto their register and are funded to progress with further work.

If you’ve not come across Buenaventura and Nexa Resources before, they’re both large operators in the region. Here’s the map of Peru that we showed you earlier. It marks the location of some of their assets relative to Tinka.

Nexa Resources

Nexa Resources own and operate the Cajamarquilla zinc smelter denoted in pink in the map above. It’s the largest smelter in the Americas and according to Wood Mackenzie, Nexa were one of the top five metallic zinc producers worldwide in 2022. They operate the El Porvenir mine to the southeast of Tinka and also own the Hilarion project to the northwest of Tinka.

Nexa Resources, a Brazilian company, has 6 operating mines and three smelters across Peru and Brazil. We’ve included the map below from Nexa Resources Investor Presentation as it shows their important Cerro Lindo mine in the south of Peru. It’s also worth noting that the Pasco Complex in Peru contains the El Porvenir mine and the Atacocha mine. These mines are denoted EP and AT in the map below and are located next door to one another, within the Pasco Complex.

We’re going to focus on the Cerro Lindo and El Porvenir (EP) mines, as well as the Cajamarquilla smelter, all located in Peru.

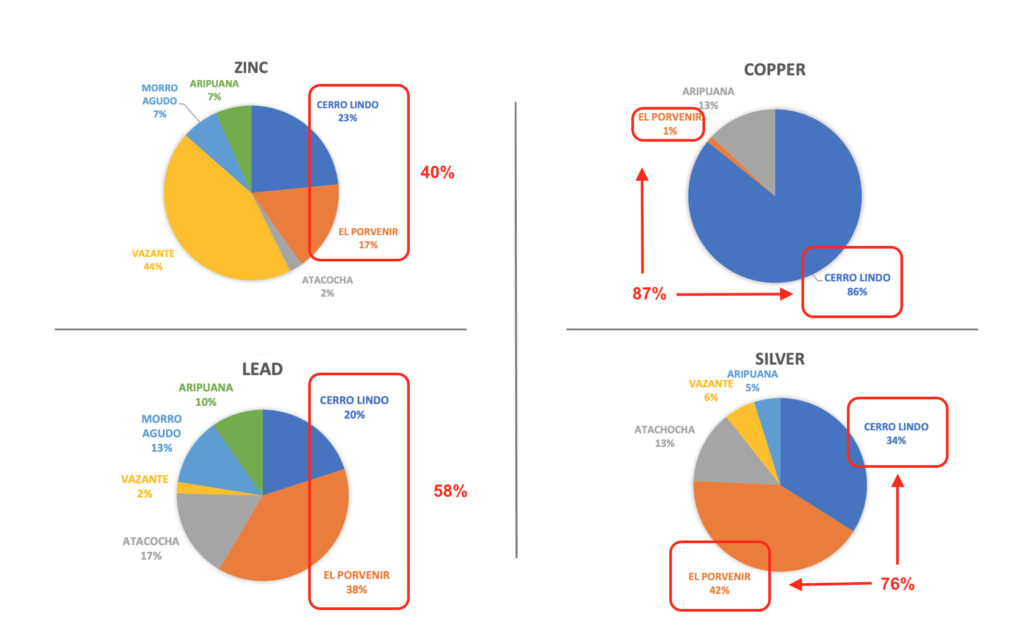

Two of Nexa’s 6 operating mines, Cerro Lindo and El Porvenir account for an OUTSIZED share of Nexa’s 2023 production profile:

Nexa’s 2023 Production by Metal and by Mine

And both Cerro Lindo and El Porvenir have been in production for some time now:

Cerro Lindo commenced operations in 2007 with a processing capacity of 5,000 tpd (1.8million tpa) and has since been expanded to a name-plate capacity of 21,000 tpd (7.7million tpa).

El Porvenir has an even longer history. A gravity separation plant was built at the site in 1953, and a flotation plant was completed in 1979. The mine’s output increased steadily over the decades, attaining a production rate of approximately 5,600 tpd (2million tpa) in 2014. Today, the mine operates above name plate capacity at 2.2 million tonnes per annum. Note: It was in 2010 that Nexa Resources (then Grupo Votorantim) gained control of the El Porvenir mine when they acquired a company known as Milpo.

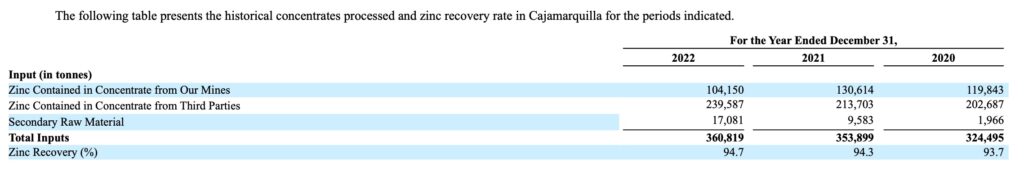

As the following extract from Nexa’s 20-F filing shows, in 2022, approximately 30% of the input material for the Cajamarquilla smelter was sourced from Nexa’s own mines. This will mostly be zinc concentrate from Cerro Lindo and El Porvenir.

It’s important to understand Cerro Lindo and El Porvenir’s key role in Nexa’s operations. Notably, their outsized performance relative to Nexa’s other mines and their importance feeding the Cajamarquilla smelter. But these mines have been steadily working through their zinc reserves for many years now.

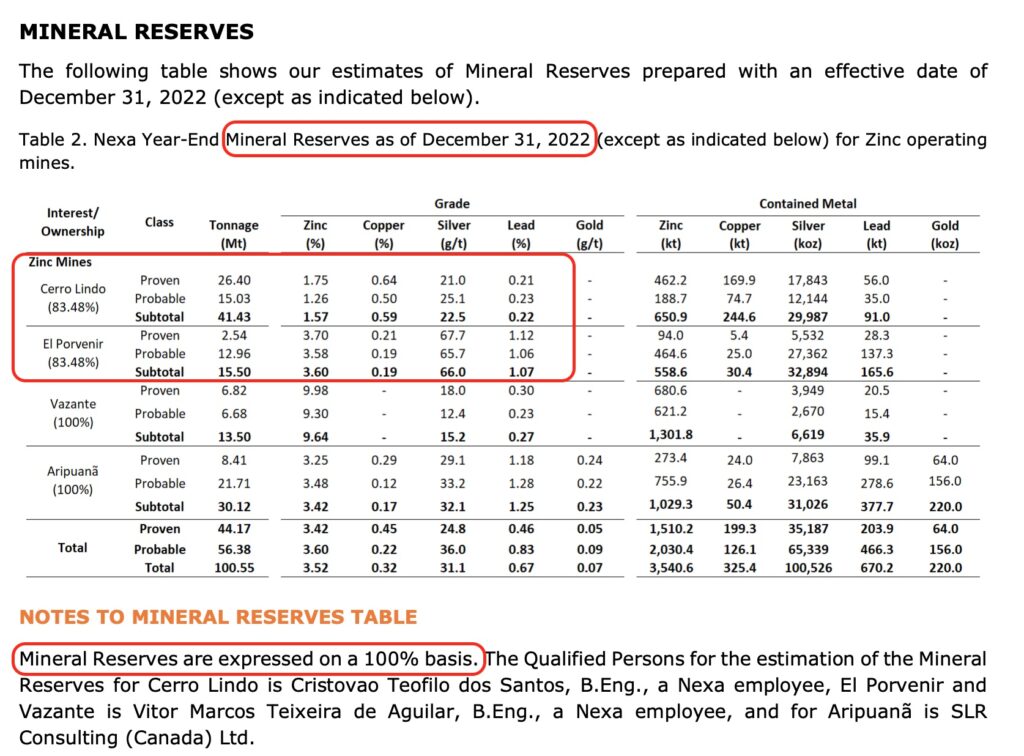

The last Reserve statement for Nexa is effective as at 31 December 2022. This statement, shown below, is presented on a 100% basis (Nexa has the right to 83.48% of the Reserves at Cerro Lindo and El Porvenir). At the end of 2022, Cerro Lindo had 41.4 million tonnes of ore left and El Porvenir had 15.5 million tonnes of ore left.

If we look specifically at Cerro Lindo, 2023 throughput was 6.0 million tonnes leaving approximately 35.4 million tonnes of ore (100% basis) at the beginning of 2024. Nexa projections for zinc production at Cerro Lindo talks of a higher through-put. If we conservatively estimate 6.2 million tonnes per annum going forward then these Reserves will last approximately 6 years, or until the end of 2029.

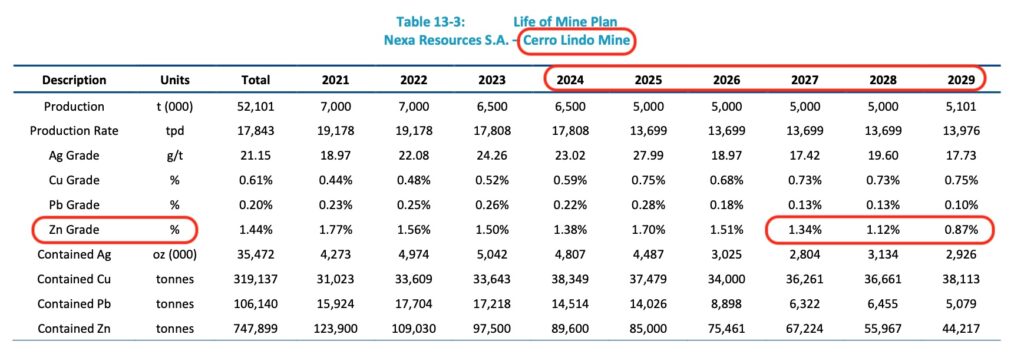

The Life of Mine plan for Cerro Lindo from the 2020 Technical Report had also estimated Reserves lasting to 2029. In terms of mine planning, this is not a long time. In fact, according to this mine plan, notice how zinc grades are expected to drop in 2027, 2028 and 2029.

This seems intuitively right, since mines usually go for the higher grades earlier in the mine plan, leaving the lower grades to later stages. This helps NPV valuations.

For El Porvenir, Minerals Reserves of 15.5 million tonnes would have likely been depleted to approximately 13.5 million tonnes by the beginning of 2024. At an on-going 2.2 million tonne per year processing rate, these Reserves should last until the end of the decade.

Both Cerro Lindo and El Porvenir might yet replace these Reserves but this is not guaranteed. As Jones Belther, Nexa’s Senior Vice President of Mineral Exploration & Business Development commented in the 4Q 2023 exploration report;

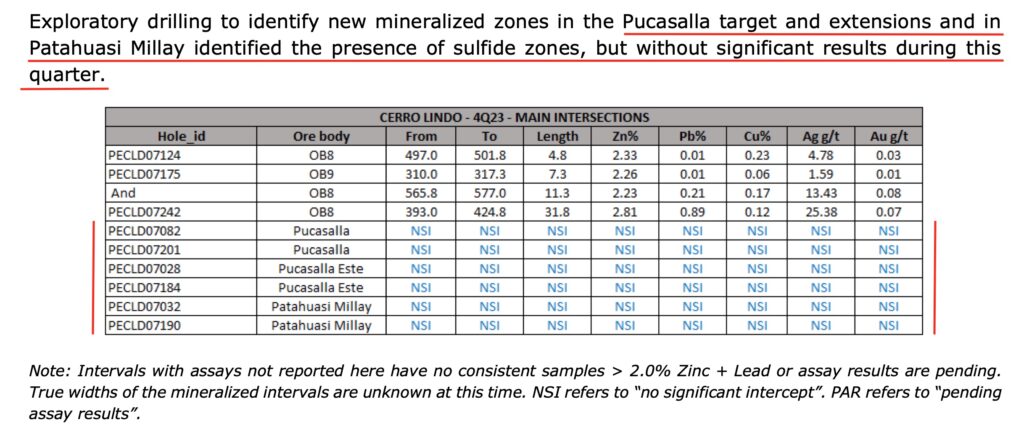

“During 4Q23 our brownfield exploration programs have progressed as planned and assay results continue to indicate that we can potentially extend the life of mine of our current operations. At Cerro Lindo, orebodies OB-8 and OB-9 continued to be extended with intersections greater than 4.0 meters as per hole PECLD07242 from OB-8 with 34.8 meters @ 2.81% Zn, 0.89% Pb and 0.12% Cu.“

The exploration report went on to breakdown the drilling at Cerro Lindo in the 4Q (see below). While just a snap shot of one quarter, Nexa made some progress at OB8 and OB9 but assays showed NSI (No Significant Intercepts) at the nearby targets, Pucasalla, Pucasalla Este and Patahuasi Millay.

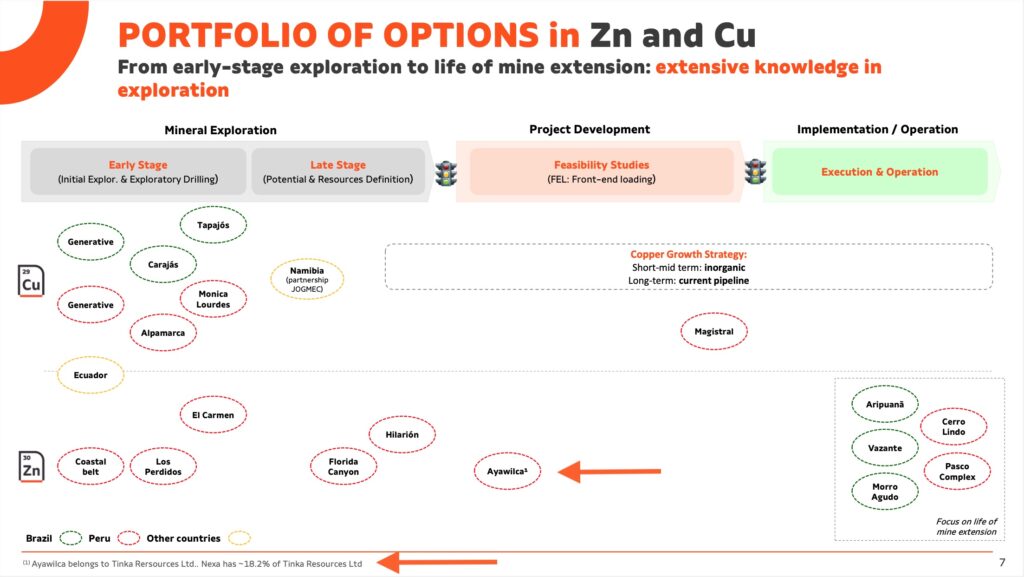

Here’s a slide from Nexa’s investor presentation from November 2023. We’ve added orange arrows to highlight the references to Tinka’s Ayawilca in their ‘Portfolio of Options’. Notice also the ‘Focus on life of mine extension’ in the bottom right hand corner that includes reference to the Cerro Lindo and Pasco Complex (El Porvenir + Atacocha).

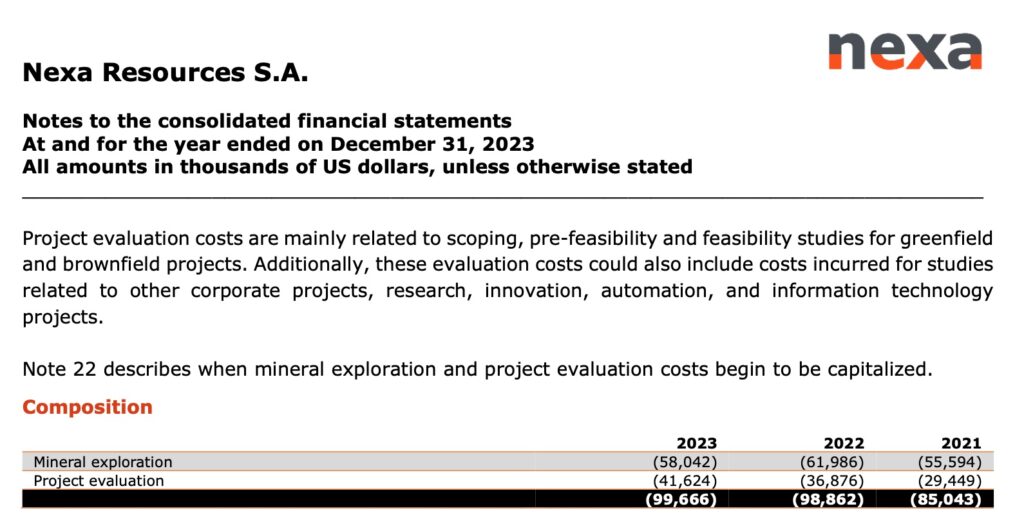

Nexa’s mineral exploration + project evaluation expenses reached US$100million in 2023. With this level of ongoing exploration + evaluation spend it’s easy to see how Tinka Resources (market cap of C$39.4m (US$53.6m) as at 2 March 2024) compares favourably in their portfolio of options.

It seems clear to us that Tinka Resources would fit neatly into Nexa’s future operating plans. But Nexa is not the only regional operator that has noticed Tinka.

Buenaventura

Buenaventura is a US$3.8billion mining company listed on the NYSE. It’s a Peruvian company and owns the Uchucchacua mine located less than 50km to the south of Tinka.

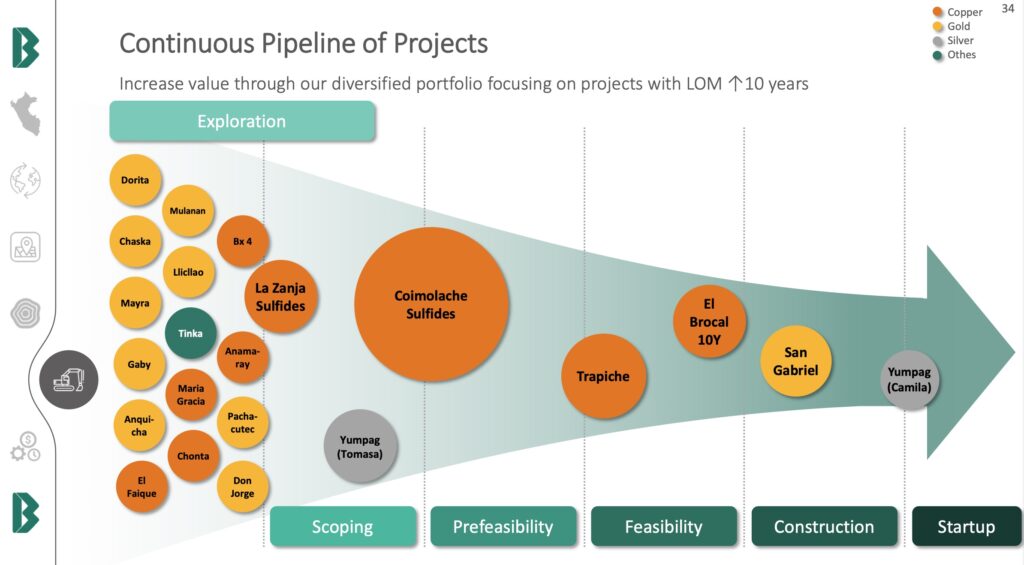

Buenaventura also feature Tinka Resources in their Investor Presentation:

In fact, Buenaventura acquired their 19% stake in Tinka back in December 2019, long before Nexa acquired their stake. At the time, Buenaventura’s then CEO commented; “Buenaventura is very pleased to make this strategic investment in Tinka. We believe that the Ayawilca project is an attractive development project that may benefit from synergies with some of our existing operations in Peru, such as Uchucchacua, El Brocal and Yumpag, as well as offering potential for additional mineral resource growth and new discoveries.“

Both Buenaventura and Nexa will be acutely aware of the progress that Tinka Resources have made at Ayawilca, and the potential of the geological system. The benefits of strong shareholders bodes well for the progress of the projects, as well as providing significant competitive tension, should either of the companies decide that they’d like a controlling stake.

Zinc Smelters and The Value Chain

The importance of zinc smelters in the value chain is important to understand.

Due to the challenges of zinc smelting, its often the case that the ‘payability’ offered by smelters to zinc concentrate producers (the amount of metal in concentrate that the smelter will actually pay for) is far lower than for other metals like silver and lead. This can sometimes be as low as 85% payability for zinc as opposed to 95% for lead and silver. For this reason, in the zinc market a large part of the value chain is captured by the smelter not the miner.

If you want to be in the zinc industry, it makes sense to vertically integrate. I.e., To own the zinc mine and the zinc smelter and retain as much of the value chain as possible.

This strategy was employed successfully by Consolidated Zinc Limited which was formed in 1949 when Zinc Corporation Limited of Australia merged with The Imperial Smelting Corporation of England. Zinc Corporation Limited had access to zinc ore from the Broken hill mine in Australia which was shipped to England for smelting.

Then in 1962 Consolidated Zinc merged with Rio Tinto to form Rio Tinto Zinc (RTZ). As Rio Tinto themselves acknowledge, the rationale for the merger was that Consolidated Zinc had ‘the much-needed financial muscle to turn The Rio Tinto Company’s dreams into reality.’

Nexa Resources will also be keenly aware of the benefits of this strategy. In fact, in 2023 the adjusted EBITDA of their smelting division totalled US$247million versus US$149million for their mining division. (Source: 20-F SEC filing).

Over the latter half of the 20th Century, the number of smelters in the West has steadily declined, driven by environmental concerns. In the US for example, there were twelve primary zinc smelters in 1970. Today, there’s just one. Smelting capacity has instead moved east to India and China.

Without smelters, a large part of the value chain is lost. It’s little wonder that most of the major diversified mining companies in the West have stepped away from zinc production and leave zinc out of their future plans. Teck are one of the few remaining diversified miners in the West with a significant zinc division. It’s unsurprising to us that they own both the mine at Red Dog AND the zinc smelter in British Columbia. As the major diversified miners continue to avoid zinc and zinc-related investment, the inevitable cyclical nature of the resources sector will, in our opinion, drive zinc prices higher over the medium to longer term.

Conclusion

We view Tinka as cheap based purely on their Ayawilca project, yet option value is provided by multiple further exploration opportunities.

If we go back to our original questions; ‘Does a mineral discovery have the potential to grow further? And is it possible that more deposits are found at depth or nearby?‘

In our opinion, for Tinka Resources, the answer to both of these questions is a resounding ‘YES!’

Tinka Resources has the potential for ‘SCALE’.

DISCLOSURE: Commodity Discovery Fund owns shares in Tinka Resources. This holding represents 3.1% of the fund and is the sixth largest holding. Tinka Resources is the funds highest conviction base metals investment.

Written by Roger Breuer, ACCA. Additional Research by Willem Middelkoop.

Thorough article. Thanks

You’re very welcome Tom! Thank you for your comment.